Global financial markets have become progressively short sighted, spurred on by ever-increasing access to real-time data and technological innovation – according to Robert Kissell in 2020, 92% of all equity market volume in 2019 was comprised of algorithmic trading [1]. We no longer live in a world in which tomorrow morning’s newspaper is the first opportunity to catch up on the latest happenings in markets – all data is available 24/7 at the click of a button. Whilst a firm grasp of current machinations in markets is often useful for active investors, too much of a fixation on short-term data and trends, and the subsequent risk of short-term capital loss, can lead long-term investors to forget why they invested in the first place.

Financial journalism is rarely a helping hand on this front, as it is human nature to have a “negativity bias” – people are drawn more to bad news than they are to good news. This inevitably leads to more negative news flow and ‘click bait’ as news outlets need to sell their product, and consumers gravitate towards negative news.

The December 2022 issue of Fortune magazine shows Jerome Powell, chair of the Federal Open Market Committee in the US, and details “The Recession Playbook” [2]. In GBP, up to the end of October 2023, the S&P Index was up +9.3%, the NASDAQ 100 Index was up 31.5%, and what was supposed to be ‘the most anticipated recession in history’ (according to many financial commentators) is yet to take place in the US. This isn’t to say that the outlook doesn’t suggest a recession, but had you chosen to sell down your US equity holdings at the beginning of 2023 based on the fear of a recession, you would have missed out on +9.3% returns (to the end of October) [3].

Furthermore, financial commentators have an increasing tendency to extrapolate short-term trends far into the future. Once a trend is so clear and obvious that it makes its way into a headline or front page, it’s a good bet that at least some of that ‘smart’ money has begun moving in the other direction.

The Bloomberg Businessweek Cover from April 2019 highlights this point nicely [4]. A decade of low inflation and low-interest rates following the Great Financial Crisis left markets with a strong feeling that any return to a high interest rate environment was a fantasy. This environment gave even enough confidence for Bloomberg to ask its readers “Is Inflation Dead”? We think plenty of investors towards the end of 2022 would have been able to tell you the answer to this question with quite some confidence.

There was absolutely no way to know that a global pandemic and a war between Russia and Ukraine would cause a global inflation issue, reaching 9% in the US, and result in the fastest interest rate hiking cycle in recent history [5]. The only conceivable course at that point in time appeared to be the trend of the preceding decade would inevitably carry on in perpetuity – otherwise known as ‘recency bias’.

This is not to say that everything we read in the media is wrong – there are plenty of speculators who get short term calls right – what is not to be underestimated is how easy it is to get it wrong. There are without doubt excellent near-term opportunities available across many different global markets, but these returns are only on offer to those who manage to both buy and sell at exactly the right moment– a very rare skill indeed.

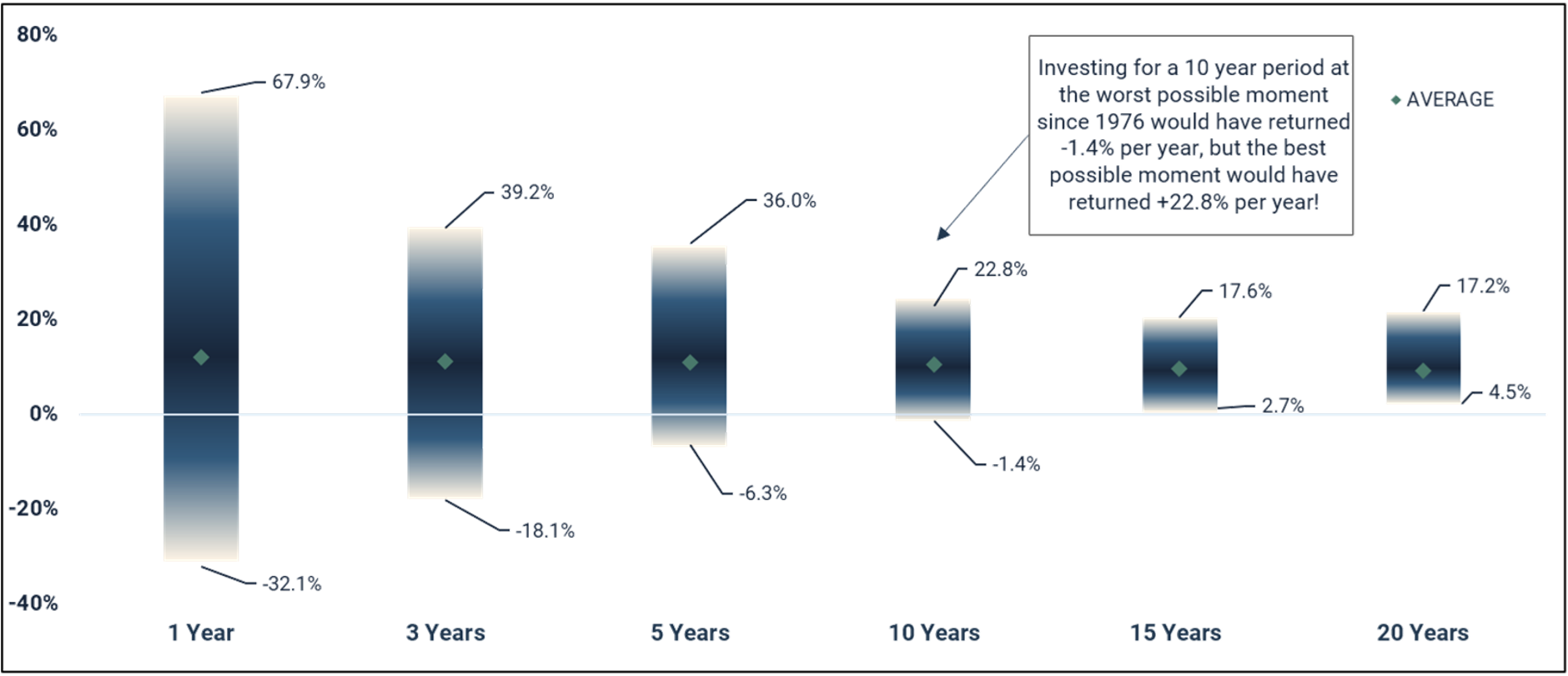

The following chart illustrates the dispersion of possible returns if one were to have invested in the MSCI World Index for various periods since 1975. The maximum possible 1-year return, if investing at the best possible time and selling exactly 1 year later would have been 67.9%. However, if one were to invest at the worst possible moment, and sell 1 year later, they would have lost 32.1% of their money. The chances of choosing the perfect moment to invest on a 1-year time horizon over 38 years are extremely unlikely, whilst the risk of such a significant downside move should one get it wrong over a 1-year period is extremely daunting. Interestingly, the average return of the MSCI World is somewhere between 9% and 12% per year between 1975 and 2023, as depicted by the light blue lines below. However, the dispersion of possible returns around this average shrinks markedly as we extend our time horizon. If investing for 20 years, even if you were unlucky enough to pick the worst entry and exit point, the lowest possible return would have been 4.53% p.a. – which equates to a cumulative +142.56% total return. If one does have a long-time horizon, the fundamental driver of returns is not timing the market, but simply being invested, and staying invested, for as long as possible.

*Data sourced from FE Analytics/MSCI [6]

The possible negative returns over shorter periods shown above plainly evidence the risks of large falls in equity markets. Significant falls in financial markets are common for a variety of reasons; asset prices regularly deviate from their ‘intrinsic value’ (that which the market is trying to ascertain) and can remain that way for a significant amount of time before correcting. A ‘bear market’ is defined as a fall in equity markets of more than 20%. Since 1945, there have been 15 bear markets – roughly one every 5 years. A fall of more than 10% but less than 20% is known as a ‘market correction’ and is much more common than bear markets. Such falls in equity markets are rightly scary for investors, as the thought of losing such a significant proportion of your money in such a short amount of time is gut-wrenching.

However, markets historically tend to rebound extremely sharply from such a significant fall. It is not simply the ability to predict a market downturn that allows one to successfully navigate such an event, as once investments are sold, the decision then needs to be made as to when to reinvest. The point at which markets bottom following a significant fall tends to be those moments where investor sentiment and news flow are at their most negative, and thus the point at which investors are least likely to want to buy back in. On 19th March 2020, the front page of the FT read “Fear grips markets as faith in government intervention runs out” – the FTSE 100 and S&P indices bottomed just days later on the 23rd [7]. To successfully time the market, investors must both predict a market fall and then buy back in at the hardest possible moment psychologically (as both levels of risk aversion and market volatility are heightened). Remaining invested throughout a market correction or bear market and avoiding the psychological pitfalls of trying to time the market, is by far the easiest way to avoid missing out on any potential future upside returns. Bear markets don’t last forever, and when they do end, they become bull markets, so selling to cash during a bear market raises the risk of missing out on significant returns once the market has bottomed.

It is often similarly hard to invest in a bull market than it is in a bear market. When stock market indices look high relative to history, investors can find it extremely difficult to pull the trigger, as waiting may result in a pullback and a better, cheaper entry point. This Economist front cover was released on January 8th, 2010 – the article heading reads “Markets are too dependent on unsustainable government stimulus, something’s got to give” [8]. Over the next one, three, and five years, government stimulus continued to flow and the MSCI World returned 11.9%, 20.8%, and 66.3% respectively [9]. Investors who held back from investing at this point would no doubt be kicking themselves down the line.

It is often well documented in the media when indices reach new highs, or stock market valuations look stretched to the upside. Entering the market when it is hitting new highs can seem unattractive, as many investors may wish to wait for a ‘better entry point’. However, in the long run, this type of decision making can also be questioned. Since February 1975, the MSCI World Index has reached a new record high in 24.8% of months [10]. It is the inherent upwards trending nature of financial markets that has caused it to hit a new high in almost 1 out of every 4 months, and the reason that the MSCI World Index has returned a whopping 16,521%, or 165x your original investment over this period! It is perfectly understandable to feel uncomfortable investing when stock markets are at record highs, but in this instance, as in a bear market, remaining invested for the long term is the safest way to benefit from the inherent upwards trending nature of markets.

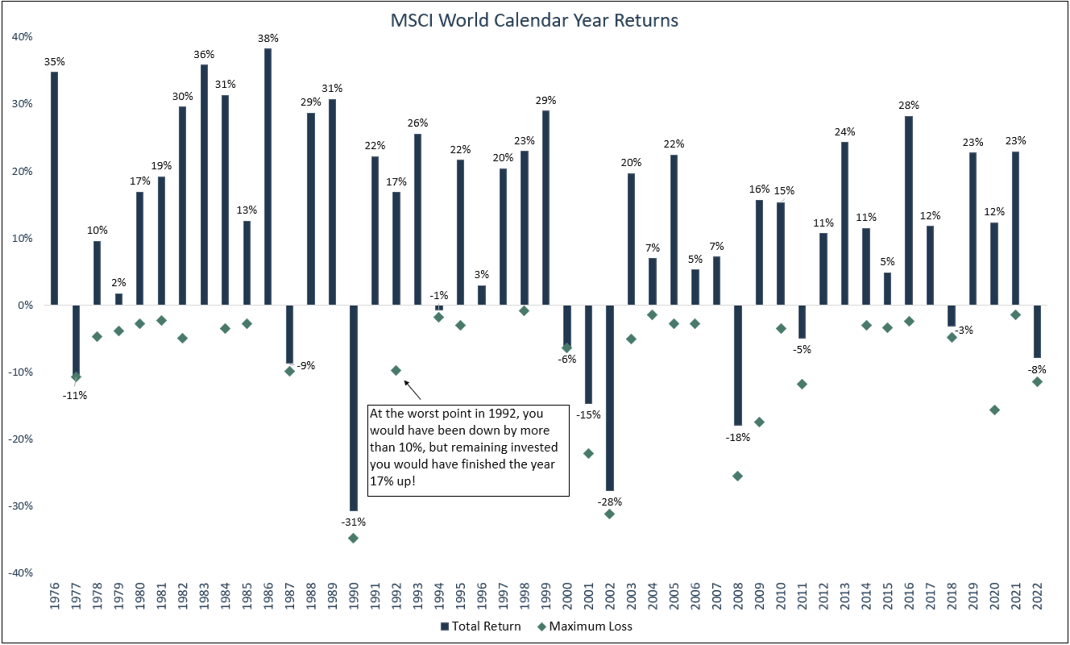

The below chart depicts calendar returns for the MSCI World in each calendar year since 1976, alongside the lowest point during that calendar year period. The first important point to note is that in 77% of calendar years, investors received a positive return – further highlighting the long-term upward-trending nature of markets. The second important point to note is the difference between calendar year returns and the maximum loss during that calendar year. There are several years in which returns are significantly positive, yet the maximum drawdown is significantly negative, most notably in 2020 (-16% to +12%) and 2009 (-17% to +16%). This supports the argument that markets often rebound quickly following a significant downturn, making it extremely hard to time, and further demonstrating that remaining invested throughout is by far the safest option.

*Data sourced from FE Analytics/MSCI

Of course, many may not have a 20+ year time horizon or may have various buckets of investments with varying time horizons. Public and private equity markets historically have a higher level of risk (volatility of returns), than government bond markets for example – investors have therefore been compensated for taking equity market risk over government bond market risk with a higher long run rate of return. There is a wide spectrum of markets offering a range of risk and return profiles. For investors with a shorter time horizon, risk-conscious multi-asset class investing can significantly help in limiting downside risks. It offers protection through diversification of asset classes, and a higher allocation to historically lower risk (or volatile) asset classes.

Financial markets are inherently cyclical, meaning they repeatedly go up and down, sometimes by significant margins, but it is imperative to remember that in the long term, despite their cyclical nature, they trend upwards. By being invested, and remaining invested, you are exposing yourself to that long-term upward trend and will eventually reap the rewards.

Article sources

Editorial policy

All authors have considerable industry expertise and specific knowledge on any given topic. All pieces are reviewed by an additional qualified financial specialist to ensure objectivity and accuracy to the best of our ability. All reviewer’s qualifications are from leading industry bodies. Where possible we use primary sources to support our work. These can include white papers, government sources and data, original reports and interviews or articles from other industry experts. We also reference research from other reputable financial planning and investment management firms where appropriate.