A debate has been raging for some time. Should investors attempt to maximise their dividends and interest income? Or should they generate returns through both capital growth and income?

In this article, we try and put this debate to rest. We have two Saltus advisers giving their views, one looking at investment considerations and the other at financial planning considerations.

On the investment side, Saltus adviser Adam Long, makes the case that investing for natural income can present additional risks to more diversified approaches, whilst potentially reducing returns. To support his case, he uses analysis from the world’s most famous investor (Warren Buffett), his lesser-known British equivalent (Terry Smith), and the world’s second largest asset manager (Vanguard).

Jack Munday brings us up to date on the financial planning considerations of both approaches. He uses sophisticated cash-flow planning software to highlight some of the differences.

This article is for information purposes and should not be considered advice. Suitable selection of investments, and their tax treatment, depends upon individual circumstances and may be subject to change. If unsure, seek advice.

Investment considerations

Most people invest to protect and grow their wealth, and some investors need cash-flow from their investments to provide for their expenditure.

To achieve this, you need to generate returns from your invested money. Returns can come in two forms:

- If your invested capital increases in value (a capital gain)

- If you receive a natural income in the form of dividends (from stocks) or interest (from bonds/cash)

Often you receive a combination of both capital growth and natural income.

Which, though, is the best way to invest to achieve your objectives?

Should you invest:

- aiming to increase the value of your capital;

- to maximise the natural income (dividends and interest) you receive, or;

- aiming for a combination of both capital growth and natural income via a total return approach?

Our view is that, unless you invest in a structure that needs to generate natural income, such as some trusts, you’re most likely better off investing using a total return approach.

Firstly, what’s good about the natural income approach?

There is something attractive about investing for natural income. You buy some stocks and bonds, and you receive a passive income that you can save, spend, or re-invest. If you really need capital, you can always sell some of your holdings. However, if you avoid doing too much of this, your capital should remain largely intact for a rainy day, for an unexpected need, or to leave to charity or loved ones.

Additionally, dividend investors rightly point out that, when you reinvest your dividends, this contributes to a significant part of the total return in time.

How significant? Very. Barclays modelled a £100 investment into UK shares as far back as 1899. If you didn’t reinvest your dividends, by 2019 your £100 would have had a nominal (not adjusted for inflation) value of £15,179. But if you had reinvested your dividends, then (ignoring tax on the dividends) your £100 investment would have had a nominal value of £2,897,759. That’s quite a difference!

This is because when you reinvest a dividend, you buy more shares, which, with any luck will grow and provide more dividends. You then reinvest these for even more dividends and even more growth, which you reinvest for even m… you get the idea. This is compounding working its magic.

However, I have three issues with this:

- This assumes the dividends are actually reinvested, which is often not the case. If you spend the dividends, on say funding your retirement or paying school fees, this effect wouldn’t happen. This is important. Most people have heard the adage that “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion”. This is Parkinson’s Law. A corollary of this law is that expenses rise to match income. That’s just a fancy way of saying many can’t resist spending their dividends even if they know they should reinvest them.

- It assumes you don’t pay any tax on the dividends, which is often not the case.

- If you are investing to grow the value of your savings, and you intend to reinvest your dividends to benefit from compounded growth, then provided you are investing in companies with attractive return potential, you should prefer not to receive any dividend at all, and for the company to retain its earnings rather than pay them to you.

There are two reasons why you should prefer the company doesn’t pay a dividend if you want to reinvest it for growth. Firstly, most investors pay tax on dividends. Because of this, they’re reinvesting less in the stock than if the company simply retained its earnings. This tax drag compounds over time. Secondly, the dividends are reinvested at the market price of the stock. Given shares normally trade on a multiple of their book value, your reinvested dividend would give you a smaller share of the company capital, than if the company simply retained its earnings.

Fundsmith LLP is a London-based investment management company founded by Terry Smith (some people refer to him as Britain’s Warren Buffett). Fundsmith attempted to quantify these differences. They looked at the annual compound rate of return of Warren Buffett’s investment firm Berkshire Hathaway from 1977 to 2017 in two scenarios:

- Berkshire reinvests all of its net income (so it doesn’t pay a dividend)

- Berkshire pays 50% of their net income as a dividend, which is then reinvested by the investor looking for compound growth

Modelling scenario one was easy since Warren Buffett’s company doesn’t pay a dividend (!).

In modelling scenario two, they assumed half of Berkshire Hathaway’s earnings were paid out to investors (so Berkshire retained half). The investors paid their tax on the dividend received and reinvested into Berkshire Hathaway at the prevailing market price (they estimated tax at 30%, which is roughly the higher rate in the UK). The impact on returns is huge.

Scenario one (no dividend) resulted in a significantly higher return, which would have resulted in a much greater value after the 40 years. As summarised below:

| Scenario 1 - no dividend | Scenario 2 - 50% dividend, reinvested | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual compound return | 19% | 14% | 5% per annum |

| Nominal value of £1,000 after 40 years | £1,051,668 | £188,884 | £862,784 |

Source: Financial Times / Fundsmith LLP

Terry Smith points out “a portion of the returns that companies generate are retained and automatically reinvested on your behalf. This creates more value than you can ever capture by reinvesting dividends, except, of course, when the reinvestment is done badly with management investing when returns are inadequate” [1]. In other words, if a company has good growth opportunities, and a management capable of effective capital allocation, then you should prefer a company to retain its earnings, not to pay them to you via a dividend for you to buy more shares.

Don’t believe Terry Smith? Let’s discuss Warren Buffett. Many proponents of the dividend approach look to Warren Buffett as an example, because he has backed many dividend producing stocks in his time. They often fail to mention that he has also backed many low yielding stocks, such as Berkshire Hathaway’s largest stock holding (Apple Inc), which currently yields about 0.7%.

So, what does Mr Buffett think about dividends as a strategy for providing both cash-flow and capital growth? Well, he outlined his thinking on dividends in his 2012 annual letter to shareholders. I’ve summarised the relevant section below (the quotations and emphasis are Mr Buffett’s own) but it’s worth reading the relevant section in full. Click here to download it.

In the note, Mr Buffett describes four things profitable companies can do with their earnings, which are not mutually exclusive:

- Reinvestment opportunities – “projects to become more efficient, expand territorially, extend and improve product lines or to otherwise widen the economic moat separating the company from its competitors… our first priority with available funds will always be to examine whether they can be intelligently deployed in our various businesses”

- Acquisitions – “can we effect a transaction that is likely to leave our shareholders wealthier on a per-share basis than they were prior to the acquisition?”

- Repurchases – “sensible for a company when its shares sell at a meaningful discount to conservatively calculated intrinsic value… it’s hard to go wrong when you’re buying dollar bills for 80¢ or less… but never forget: in repurchase decisions, price is all-important. Value is destroyed when purchases are made above intrinsic value”

- Dividends – he works an example: Assume you and Mr Buffett are equal owners of a business with $2 million of net worth (the net worth being the value of the company’s assets minus its debts). This business earns 12% on its net worth as well as on any reinvested earnings. As it’s a “sensible” company, investors will buy shares in the company on the market at some multiple of its net worth, he assumes at 125%. This means the value of the shares each of you own is $1.25 million ($2 million net worth x 125% = $2.5 million total value of the shares. You own half of it with Mr Buffett, so your shares are worth $1.25 million each).

Scenario one: dividend approach

Wanting to receive cash from the business, you initiate a dividend policy where one third of the company’s earnings are paid as dividends and two thirds are retained in the company to grow at 12%.

In the first year, you would both receive a dividend of $40,000, and this would increase as the company grows.

By the end of year 10, your dividends would be $86,357 each, while you and Mr Buffett would each have shares worth $2,698,656. “And we would live happily ever after – with dividends and the value of our stock continuing to grow… there is an alternative approach, however, that would leave us even happier.”

Scenario two: “the sell-off approach”

Leave all earnings in the company and instead sell 3.2% of your shares annually to meet your spending needs.

In the first year, you would receive $40,000 each, and your percentage ownership of the company would reduce because you’re selling shares to generate cash-flow.

By the end of year 10, you would each own 36.12% of the business. You would each have shares worth $2,804,425, and you would each receive $89,742 from your annual policy of selling shares.

A summary of the scenarios is below:

| Your year 1 cash-flow | Your year 10 cash-flow | Value of your shares after 10 years | Your year 10 ownership | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1: dividend approach | $40,000 | $86,357 | $2,698,656 | 50.00% |

| Scenario 2: "sell-off" approach | $40,000 | $89,742 | $2,804,425 | 36.12% |

| Additional value before tax: | +$3,385 | +$105,769 |

By choosing the “sell-off” approach as opposed to receiving dividends, even though you own a smaller percentage of the company at the end, you would have both more capital invested and you would be receiving higher annual payments. This is because the company retained more of its earnings, which it then compounded.

There’s more… in his letter, he points out three additional arguments for the “sell-off policy”.

- In the example, the two assumptions were conservative. The US stock market earns considerably more than 12% on net worth, and sells at prices far higher than 125% of that net worth (399% at the time of writing!). He says that, if his assumptions are exceeded, “the sell-off policy would have produced results for shareholders dramatically superior to the dividend policy”.

- Selling shares gives you the ability to flex your cash-flow up or down based on your actual needs, whereas dividend policies apply for all shareholders. Most investors can’t influence dividend policies, but they can decide how many shares to sell. Mr Buffett points out that, while a dividend investor could use his dividends to buy more shares if he didn’t need all the cash, “he would take a beating in doing so: he would both incur taxes and also pay a premium to get his dividend reinvested. (Keep remembering, open-market purchases of the stock take place at 125% of book value.)”

- The tax consequences of the dividend approach are “usually far inferior – to those under the sell-off program. Under the dividend program, all of the cash received by shareholders each year is taxed, whereas the sell-off program results in tax on only the gain portion of the cash receipts”.

Total return managers have more investment options

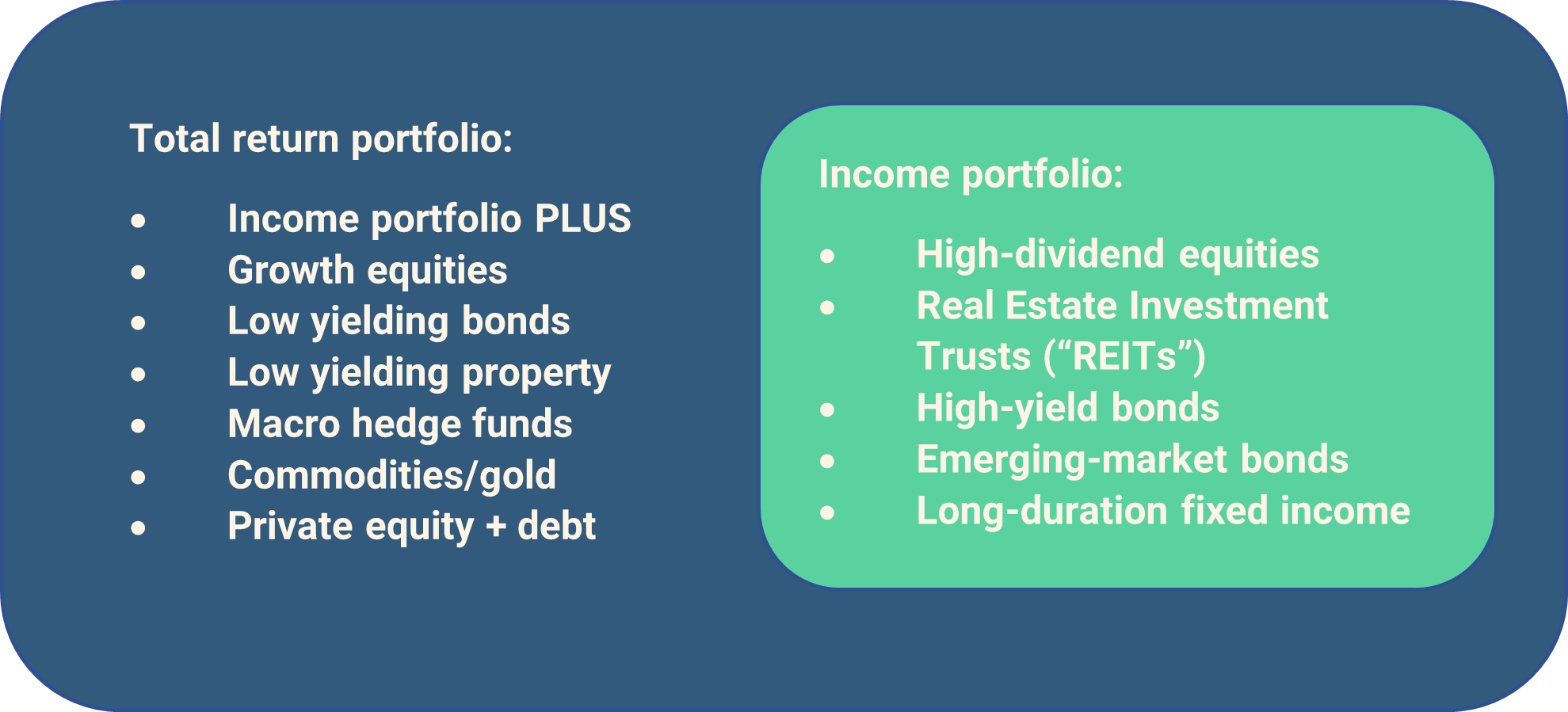

Total return managers can invest in everything income investors can invest in, and a lot more, as indicated below:

As total return managers aren’t constrained, they have a clear advantage. In addition to income generating assets, within a total return portfolio, exposure can be given to low yielding assets that are beneficial to the investor. These include gold, hedge funds, private assets, and commodities. These were some of the best performing assets last year.

There are times when income generating assets are in favour, and total return managers can tilt portfolios in that direction. But income investors don’t have this flexibility and there are times when they will give up returns as a result.

In fact, the focus on natural yield has resulted in many income portfolios missing out on some of the best performing sectors of the global stock market. Reflecting on the companies who have provided the real wealth creation of the past decade, it hasn’t been the oil and gas companies, or the tobacco companies, of an income portfolio. They’ve been software companies, chip-makers, electric vehicle makers, e-commerce businesses, and high-end consumer discretionary companies – many of these have created significant wealth for their shareholders, and many don’t even pay a dividend! Since they don’t pay a dividend, investors looking for natural income to fund their retirement likely didn’t have exposure to these high growth areas, and they would have missed out on the opportunity to increase returns.

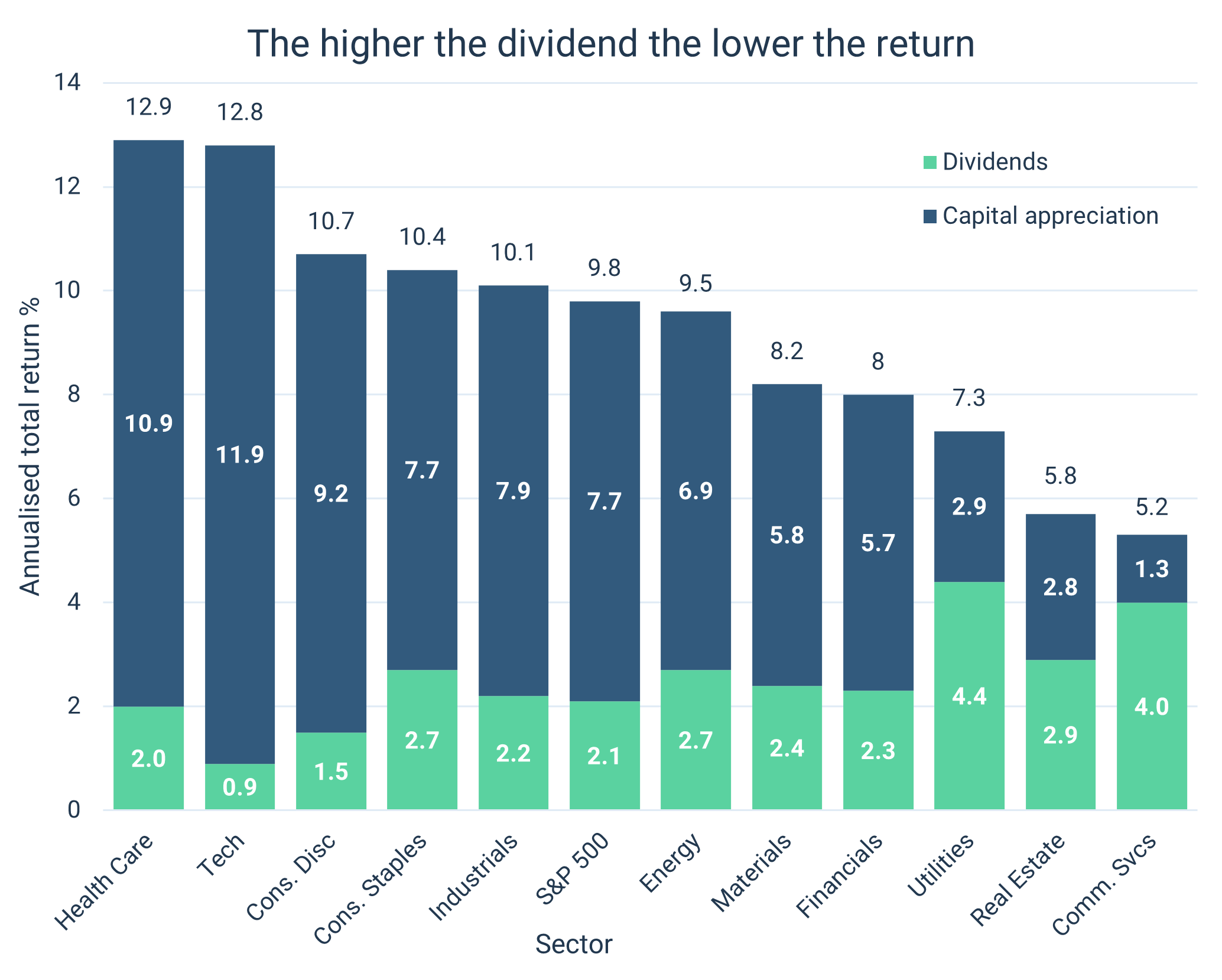

JP Morgan assessed the performance of US stocks over a 25-year period (as measured by the S&P 500). They found that high dividend stocks had lower returns in the period they reviewed, as shown below:

Source: JP Morgan

This isn’t just an American phenomenon. Looking at a global stock index you can see significant outperformance of all stocks versus high dividend yield stocks, over time periods longer than one year (these numbers include reinvestment of any dividends), as shown below. The first stock index is all stocks within the MSCI All Country World Index. The second is the “high yield” version of that same index, i.e., only those companies who are deemed to pay a high dividend are included:

| Stock Index | 1yr | 3yr | 5yr | 10yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCI All Country World Index Total Return £ | -8.1% | 23.9% | 45.1% | 191.2% |

| MSCI ACWI High Dividend Yield Total Return £ | 4.2% | 18.4% | 39.2% | 147.7% |

Source: FE Analytics, data to 31 December 2022

The above shows significant long term outperformance of the broader index, when compared to the high yielding stocks. It does show high dividend stocks outperforming other stocks in the last year, but this doesn’t necessarily support income investing as a permanent theme. A high-quality “total return” investment manager would try to tilt their portfolio to high dividend stocks when it’s advantageous to do so. An investment manager focused solely on dividends, though, most likely couldn’t advantageously tilt their portfolio the other way, given the restrictive mandate to maximise natural income.

Risks with income investing

There are additional risks when it comes to chasing income:

1. Missing out on opportunities to protect and grow wealth (see analysis above)

2. A lack of diversification can hurt

Don’t just take my word for it, the $7 trillion investment firm Vanguard looked at high-yield portfolios, outlined the appeal of each of the asset classes they typically contained, and summarised the risks as follows:

| Asset class | Appeal | Risks |

|---|---|---|

| High-yield bonds | Higher yield premium than investment-grade bonds | Higher probability of default. Lack of diversification |

| Emerging-market bonds | Higher yield premium than investment-grade bonds | Greater risk because of less-developed political systems and fluctuations in emerging-market currencies. Lack of diversification. |

| Long-duration bonds | Higher yields | Less diversified and subject to greater volatility than a bond portfolio that is allocated across the yield curve |

| Real Estate Investment Trusts ("REITs") | Higher yields and lower costs | Amplified exposure to the risks of a narrow sector of the stock market and economy |

| High-dividend-paying equities | Higher yields | Less diversification, as these stocks tend to be more concentrated in a few defensive sectors |

Source: Vanguard

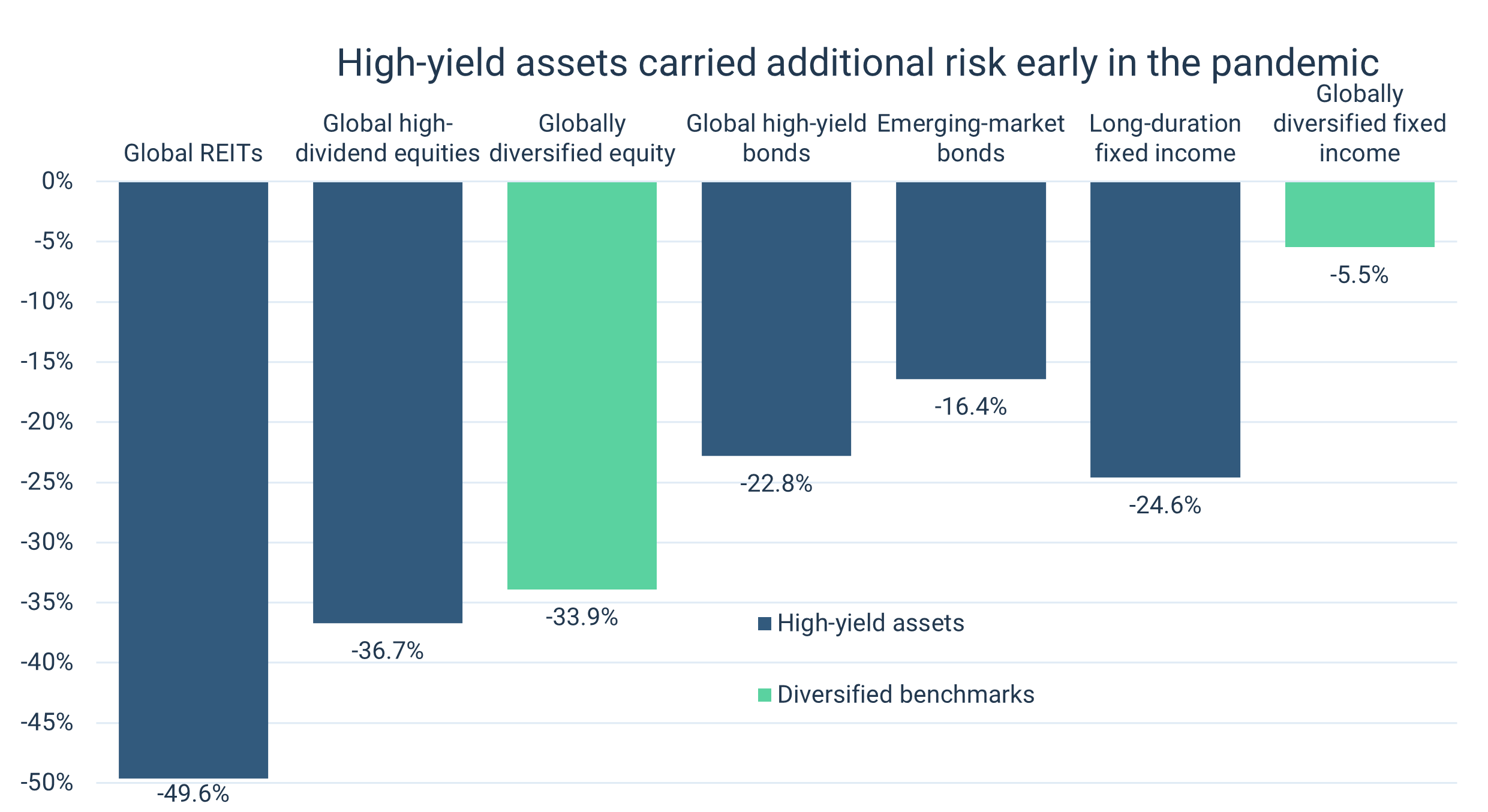

They point out that “tilting a portfolio toward higher-yielding assets and away from traditional asset classes only magnifies losses during times of market stress, including the recent market swings of 2020”, as shown below.

The below chart shows how high yielding assets (in blue) fell more than more diversified assets (in green) during Covid.

Source: Vanguard [2]

Meaning that, had you tilted your portfolio towards high yield stocks and bonds (so, owned the blue bars) before the pandemic, this is likely to have resulted in a bigger fall in the value of your portfolio than had you had a diversified portfolio (the green bars).

This was a repeat of an earlier study where Vanguard looked at returns during the global financial crisis, where they found the exact same thing: high yielding assets had larger falls than lower yielding assets.

3. Unexpected falls in dividends or interest payments

There are times when companies significantly reduce their dividends, like they did during the Covid period, and after the great financial crisis of 08/09. Investors relying on those dividends for spending would have had to draw on other assets.

Summary

In summary, the total return approach is superior for three reasons:

- Total return investors have more investment options, which means a greater ability to diversify portfolios, potentially boosting returns whilst lowering volatility and reducing drawdowns. Conversely, investing for natural income exposes investors to additional risks, because of the narrower investment options

- Provided the company you’ve invested in gets a decent return on equity, then you’re likely better off leaving the money invested, not receiving a dividend, which can increase your returns (the analysis of Warren Buffett and Terry Smith)

- Total return investors typically pay less tax than those seeking natural income. Even if we assume the returns are the same, investing in a total return approach reduces the tax burden, so investors have more to save, invest, and spend. I’ll leave it to Jack (the financial planner) to expand on this

So, unless you’re mandated to invest for dividends, then staying flexible in approach is most likely to be the best option. There are times when income generating assets will be in favour. But permanently pointing your portfolio towards income generation could reduce the likelihood of you achieving your investment goals. This is because your income could suddenly fall, you may miss out on higher growth opportunities, and, because of the narrower investment options, you could miss out on opportunities to diversify your portfolio and suffer larger losses as a result.

Financial planning considerations

Whether you are an experienced investor, or someone who barely takes an interest, there will be a common goal for your money: making it work properly for you. “Properly” is a very subjective term as the reality is that there is no hard and fast answer. Planning is more of a fine art than an exact science. However, ultimately everyone needs their assets to work in the most suitable way for their own objectives, and that’s the common theme.

Now, unless you are lucky enough to have a substantial form of guaranteed income, a driving focus for your assets and planning will be how to best cover your expenditure needs, either now or in the future. The hunt for “yield” can be a lot riskier than the hunt for withdrawals. A natural yield is often classed as more sustainable as you are not selling down units and instead just skimming from the top. However, as referenced earlier by Adam, there are significant limitations to investing in income funds, and this continues into planning with them.

A generational change?

In light of the current political turmoil and revolving doors we have seen at No.10 in recent months, it’s probably a fitting time to remember that the tax landscape has in fact changed over the years. When we look back, in the past eight years alone, there have been three changes to the taxation of dividends… four, if you count a reversal… and five with the new budget changes coming in April 2023.

| Years | Tax treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre 2016 | Basic rate | 0% |

| Higher rate | 25% | |

| Additional rate | 30.56% | |

| Pre 2013 additional rate | 36.11% | |

| 16/17 - 17/18 | Nil rate allowance | £5,000 |

| Basic rate | 7.50% | |

| Higher rate | 32.50% | |

| Additional rate | 38.10% | |

| 18/19 – 21/22 | Nil rate allowance | £2,000 |

| Basic rate | 7.50% | |

| Higher rate | 32.50% | |

| Additional rate | 38.10% | |

| 2021/22 | Nil rate allowance* | £2,000 |

| Basic rate | 8.75% | |

| Higher rate | 33.75% | |

| Additional rate | 39.35% | |

| 2023/24 | Nil rate allowance* | £1,000 |

| 2024/25 | Nil rate allowance* | £500 |

All of this would be redundant if you had full control over your income strategy. If you’re taking natural income from your investments, though, you do not. Dividends are taxed last in a priority order, which means that they will always be liable to your highest level of personal tax (the leap from basic rate to higher rate in the dividend taxation is no accident). This takes an appealingly low figure of circa 8.75% and turns it into a sustainability eroding 33.75% or higher. In light of the additional rate threshold now reducing to £125,000, this also means you’re paying an additional rate of £25,000 sooner (and entering the tax compounding territory of the 60% tax trap – Earning over 100k? How to avoid the 60% tax trap | Saltus)

The reduction in your tax-free dividend allowance from £5,000 to £2,000 also had a heavy hitting effect to the ongoing efficiency. Let’s take the mean dividend yield from the S&P 500 of 4.23% [3] to work an example:

- With an allowance of £5,000, an investor could have an unwrapped portfolio of £118,200 (rounded up) and not have a tax liability from the 4.23% income paid out

- The reduction to £2,000 now means that the figure falls to £47,300

You may conclude from this that it’s a small issue and that, in fact, you can circumvent this by utilising alternative tax wrappers. That’s definitely the aim of the game but we have to work within the planning tramlines we have in the UK. This means that those tax-efficient dividend wrappers like pensions and ISAs have a limited level of funding they can receive each year (with pensions becoming even more punishing the more you earn).

In isolation, the dividend allowance will have reduced by 90% (£5,000 down to a proposed £500) by 2024/25. In our S&P example alone, that would mean only £11,820 could be held without the tax liability arising. Looked at from a different angle, it means the initial £118,200 portfolio yielding 4.23% would now create a higher rate tax payer and an additional £1,518.70 tax bill for the pleasure of holding their portfolio.

The total return investor also holds a further ace up their sleeve: the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) allowance. In fact, if you’re planning as a family, you can have potentially two lots of this valuable allowance. So, what is this? Individually, we all get a CGT annual exempt amount of £12,300 (2021/22 tax year) and you only pay CGT if your overall gains for the tax year (after deducting any losses and applying any reliefs) are above the annual exempt amount [4]. In reality, this means that the total return investor can reset their book costs as they go along.

In practice:

- £100,000 purchase price of investments

- Growth for 1 year of 5% would equal an end value of £105,000

- £5,000 of gain falls within the CGT annual exempt amount of £12,300 and therefore the gain can be realised to reset the book cost

- New book cost of £105,000 and no tax paid

This allows a lot more creative control over the tax leakage of your planning as opposed to the impact of direct natural income, which you pay dividend tax on, despite selecting reinvestment. Below is an example of the same growth but split between dividend yield and capital growth.

| Type | Investment | Growth | Dividend yield | Tax paid (higher rate taxpayer) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-yield investment | £100,000 | 3.50% | 1% | £0 |

| High-yield investment | £100,000 | 1% | 3.50% | £506.25 |

Investing for total return and using your CGT allowance allows considerably more control. Conversely, an investment focused on direct natural income negatively impacts long-term value due to the dividend tax you have to pay, despite choosing to re-invest.

Now, CGT has taken a bit of a hammering recently and will likely continue to do so. Annual exempt allowances are falling to £6,000 per person in the 2023/24 tax year and down to £3,000 in 2024/25. Let’s put this into perspective:

- £6,000 allowance still creates a tax-free resetting of the book cost in the above scenario as it is higher than the 4.5% growth

- £3,000 allowance on the surface is cause for concern. However, when you add the power of planning as a family unit, this still allows for the combined growth to be reset without charge

- For those with single allowances only, let’s also appreciate that CGT is taxed at half the rate of income tax currently and still 6 times higher than the proposed dividend allowance!

A further trip down memory lane reminds us that it was only in 1995 that pensioners were able to take capped drawdown from their retirement products, as opposed to an annuity, pre-age 75. A 20-year gap then followed until we were allowed to take flexible drawdown and not be forced into a stressed annuity rate at age 75. Couple this with significant rises in ISA allowances, and you suddenly have a much broader horizon for financial planning. This horizon means that you can be more efficient with your tax planning and structuring. Remember, you can invest in all of the same dividend producing vehicles in a total return approach but with a broader level of diversification.

What all of these changes mean is that efficient planning is now in the hands of everyone as opposed to high net worth individuals alone. The mentality towards wealth and planning has shifted and, therefore, having the open discussion about your investment approach needs to follow. There will be scenarios where natural income is king but, with the flexibility to control your tax leakage and sustainability via multiple tax wrappers and a diversified investment approach, you can ensure that you are utilising those same high yielding instruments within a total return approach. This results in practice as a potential 10%+ capital increase when assessing a standard client approach.

Case Study

To put these statements to the test, and for our own curiosity, we have created a generalised scenario which is representative of someone with a reasonable amount of wealth but with very simplistic self-planning.

Scenario 1: Total return investing

| Asset | Starting value | Yield | Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | £75,000 | N/A | N/A |

| SIPP | £400,000 | 1% | 3.5% |

| GIA | £1,000,000 | 1% | 3.5% |

| ISA | £350,000 | 1% | 3.5% |

SIPP = Self Invested Personal Pension, GIA = General Investment Account, ISA = Individual Savings Account

Scenario 2: Natural income investing

| Asset | Starting value | Yield | Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | £75,000 | N/A | N/A |

| SIPP | £400,000 | 3.5% | 1% |

| GIA | £1,000,000 | 3.5% | 1% |

| ISA | £350,000 | 3.5% | 1% |

We’ve then applied some reasonable assumptions to the two scenarios and assessed the outcomes using cashflow modelling software.

In the spirit of fair competition, the overall growth of the two portfolios is the same at a conservative 4.5% running to the ONS average age for a male of 82 [5].

Pensions have been left as the last withdrawal source, with the view of generational planning, and the GIA is funding the ISA allowance until exhausted in both scenarios (all other assumptions are available on request).

The client in both scenarios is age 50 and working for the next five years with a salary of £115,000 before tax. From 55 onwards, they retire with an inflation-linked expenditure need of £65,000 after tax.

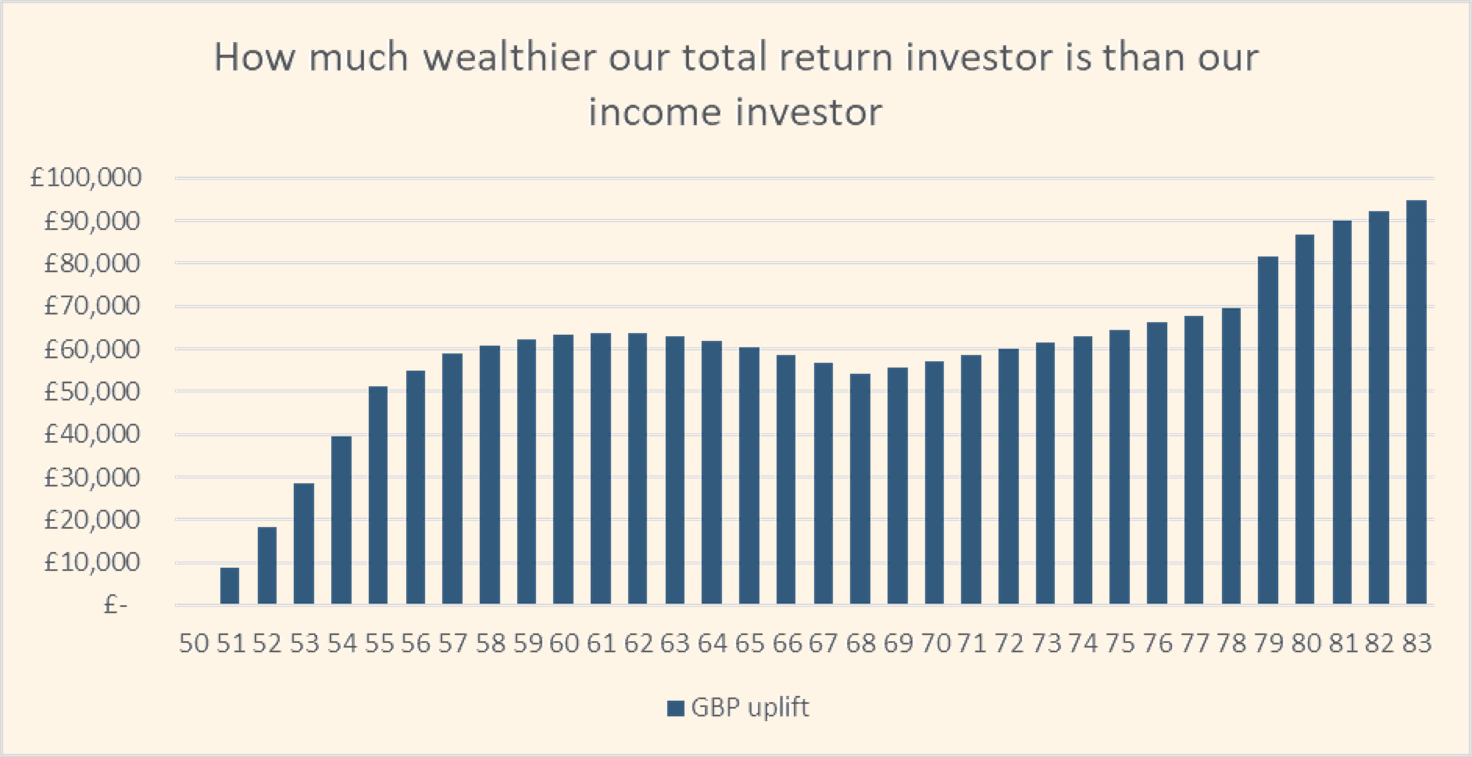

The conclusion from the cashflows was that the income investor will run out of money 18 months before the total return investor, whilst utilising the same planning and tax wrappers. This is the compound effect of tax leakage alone and could be exacerbated by the lack of investment options to the income investor, as we touched upon earlier.

The chart below shows that the total return investor generates an extra £50,000 after just five years and after 31 years they are a whopping £90,000 better off.

We also extrapolated the amount of tax that may be due within our two scenarios:

The income investor – £506,782

The total return investor – £484,634

That’s a tax saving of £22,148 over the life of the financial plan and, when coupled with the £94,815 uplift in value, the total return investor comes out with an additional £116,963.

To contextualise, ranging from boring to exciting, that’s:

- 79 extra years of standard expenditure

- A two-bed terrace house in Stoke-on-Trent

- A second-hand Sunseeker AXOPAR 25 (and change)

- Two all-inclusive around the world cruises

This example isn’t just to show you what luxury items you may be missing out on. In fact, the income investor can likely have these too as long as they engage in planning early and ensure that the investment solutions and financial planning are working hand in hand towards their individual objectives. We are not saying all income investors are going to run out of money and it’s all doom and gloom, instead, it’s about what extra value you could be missing out on and how that translates to your own quality of life.

With different scenarios and different objectives, the income investor may likely come out on top in a few cases. However, the core of the matter is that there are quite literal savings to be had by tailoring your finances to work for you.

The exceptions

As mentioned earlier, this is really about your planning needs as opposed to having an overt bias towards a specific type of investing. Like everything in this world, there is a time and place for the natural income strategy. As with the personal tax tramlines, there are also restrictions for life tenants and remaindermen of specific trust vehicles. Where there is a reliance by trust law on natural income only, it’s important that an appropriately tailored income fund selection is utilised. This could also be factored into the underlying beneficiaries tax position and is worth consideration. If the trust income is mandated to the beneficiary directly, they are liable to the tax position yet have no control over the income producing assets.

If inheritance tax (IHT) is a strong driver for you but you can’t quite afford the aggressive gifting approach, through either affordability or health concerns, then natural income could also work in your favour. When gifting from regular income, the payment can be an allowable gift and is exempt from IHT as long as you “can afford the payments after meeting your usual living costs.” [6] Therefore, natural income above and beyond your spending needs can be gifted away regularly to help the family and to reduce your estate. We do stress though, that this still needs to be part of a well-rounded financial plan, otherwise all the potential tax issues referenced throughout this article still apply.

To summarise

The above analysis suggests that income investing can reduce returns, expose you to additional risks, and cause you to pay more tax. For these reasons, unless you’re mandated to seek income, you’re probably better off staying flexible, and looking for the best total return possible.

Or, as legendary investor Terry Smith said: “dividends aren’t at all important to us. You should invest in equities for the greatest total return you can get – that’s the growth of the share price plus any income, and if you need to spend some money, sell some of your holdings, which I know isn’t rational to some people, but I assure you is the correct way to do this”.

Or more succinctly: “natural yield: a totally bonkers retirement income strategy”. (A Okusanya – Beyond the 4% rule: the science of retirement portfolios that last a lifetime)

Article sources

Editorial policy

All authors have considerable industry expertise and specific knowledge on any given topic. All pieces are reviewed by an additional qualified financial specialist to ensure objectivity and accuracy to the best of our ability. All reviewer’s qualifications are from leading industry bodies. Where possible we use primary sources to support our work. These can include white papers, government sources and data, original reports and interviews or articles from other industry experts. We also reference research from other reputable financial planning and investment management firms where appropriate.